When talking about Mount Kilimanjaro people usually focus on its height and location. Most people think is tropical since it is located near the equator. They also think it is warm since it is in Africa. However, this is not the case. The mountain—the tallest in Africa—is capped with snow and ice. It is 19,341 feet tall.

Additionally, the seasons are reversed since it is in the southern hemisphere. July is mid-winter in Tanzania. To be more accurate, there aren’t traditional seasons in Tanzania, rather there are two seasons, the wet/rainy seasons and the dry seasons.

The long rainy season is from mid-march to the end of May. The short rainy season occurs throughout November.

The rest of the year January-February, June-October, and December are considered the dry seasons.

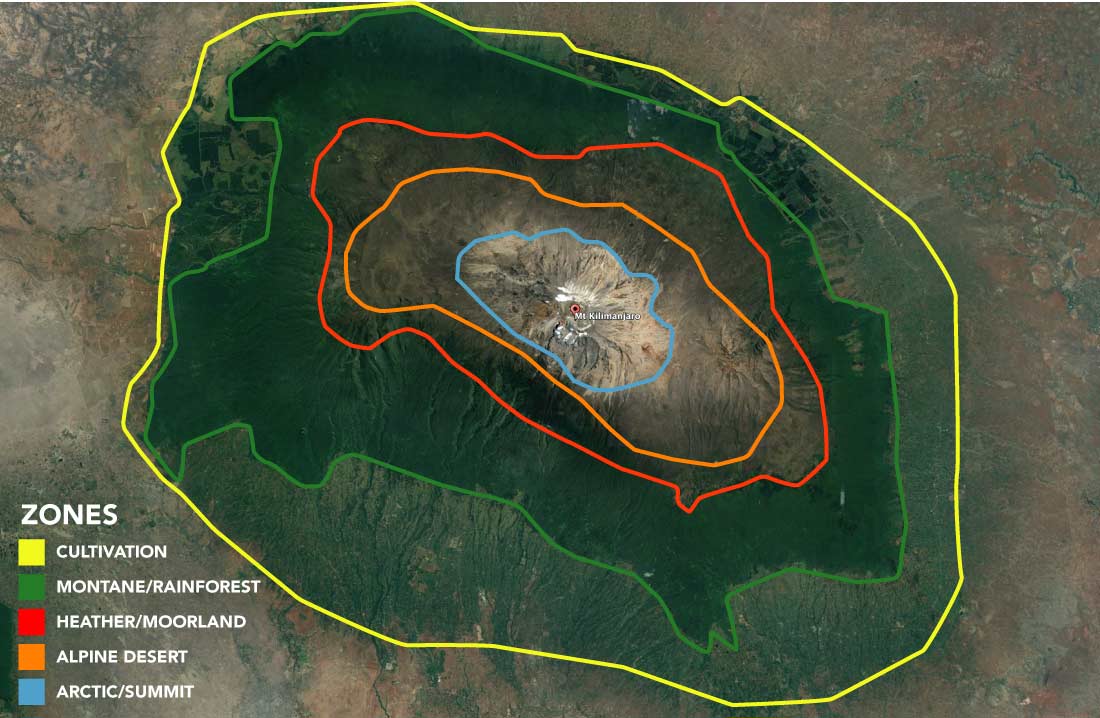

Viewed from a top-down view, Mount Kilimanjaro becomes compelling for a different reason. To get to the summit, you must pass through several distinct climate zones on Kilimanjaro. These zones are visible from space.

The Cultivation Zone

The lowlands surrounding the mountain are where people grow crops. There is little natural vegetation on the foothills. Instead, people have taken advantage of the volcano’s rich soil to grow maize and beans, and to establish home gardens and coffee farms. This zone is known as the Cultivated zone it is approximately 2,600 ft to almost – 6,000 ft. This region of the mountain receives the most annual rainfall. It also has many rivers formed by glacier run-off from the top of Kilimanjaro. Small Chagga villages and farmland make up this zone. These villages are where many of the porters and guides you will see on the mountain come from. You will drive through these villages on the way to your climb. Coffee is the main crop in this region. Some of Africa’s best coffee comes from the foothills of Mount Kilimanjaro. Bananas, avocado, papaya, and other fruit are also grown on the lower mountain.

Montane or Rainforest Zone

Only small corridors within the forest belt were protected when the park opened in 1973. In 2005, the park boundaries were redrawn to include more of the montane forests.

Most of the rain on the mountain falls on the south and the east side. The forest is much thicker here than the Kenya side on the north side of the mountain. The flora and fauna are diverse. However, the animals are very elusive. Monkeys (both Blue and Colobus) are prevalent on certain routes, while olive baboons, leopards, mongooses, elephants, bushbabies, black rhinoceros, giraffes, and buffaloes are known to visit the mountain’s slopes. They are rarely seen.

The best places to see wildlife are in the upper reaches of the jungle as you exit the rainforest. The rainforest is simply amazing. The colors seem more vibrant than any forest you have ever seen. Furthermore, the trail is flanked by deep gorges of emerald blankets of every shade of green imaginable. Rising majestically out of the forest floor are twisted, ancient trees draped in coats of moss. When there is a break in the foliage, you get to watch the clouds weave a path through the treetops. The temperatures in the forest are usually mild and if it’s going to rain on your climb, it will be here.

Heather and Moorland Zone

As you move up Kilimanjaro, the dark green areas transition to a band of green-brown known as the Heather and Moorland zone. Vegetation still survives here, but it is nothing like the wet, humid forests found at lower elevations. The climate is colder and less humid, and the landscape is full of shorter, hardier plants such as the mountain’s iconic Senecios and Lobelias. The moorland landscape starts around 9,000 feet and extends to about 13,000 feet, above which vegetation becomes even more scarce.

The temperatures here are erratic. The daytime temperature can soar above 100° F yet drop below freezing (32° F) at night. These temperatures combined with less rain, gusting winds, giant heathers, wild grasses, and a rocky trail replaces the rainforest very quickly.

Some of the heather shrubs can grow to over 30 ft. high. As you continue your ascent tall grasses replace the heather as you enter into the Moorland zone. Large fields of wildflowers cover sections of the mountain and you will often see clouds floating at your eye level. Expect amazing blue skies at the upper end of this zone. There will be little cloud cover to protect you from the sun’s UV rays. Brings plenty of Sunscreen. Now that you are above the cloud line the views of the rainforest below and the top of Kilimanjaro 7,000 ft above are simply breathtaking. After sunset, the sky will be lit up with an innumerable amount of stars. It is a truly peaceful environment.

Alpine Desert Zone

Above the Heather/Moorland region is the Alpine Desert. It can be warm, even hot, during the day, but below freezing at night. This zone is relatively inhospitable. It is also known as the Highland Desert zone. The elevation begins around 13,000 ft. and continues up to 16,000 ft.

This region is a strange place, it is truly deserving the title of Desert. The annual rainfall is less than 8 inches a year and what plant life exists at this altitude has to survive with the oppressive sun and sub-zero temperatures—all on the same day. The plant that does survive this harsh environment is the Groundsel tree. The odd plant is scattered throughout the Barranco Valley.

This area also has evidence of its tumultuous past. Fields are littered with volcanic rock of all shapes and sizes. You are now close enough to the cone of Kibo to see the vast glaciers that cling to its steep ledges. It has deep gorges on the slopes and breaches in the crater rim where molten lava blasted through during prehistoric eruptions. The landscape is barren. Be sure to bundle up at night. At this altitude, the mercury dips well below freezing and you may wake up to frost on your tent in the morning.

Arctic Zone

You will follow the crater rim as it rises beside a massive glacier to Uhuru peak, you finally approach the sign that signifies the feat you just accomplished. You have made it to the Roof of Africa.

Climbers who make this journey are rewarded with an expansive view. To the east, the peak of Mawenzi is just visible behind the crater rim and to the north, Kenya spreads out on the horizon.

The Crater is a fascinating place and if you still have some energy in reserve, it’s well worth making the short trip to the inner crater. Inside is the Ash Pit. It is 1,100 ft. across by 393 ft. deep, it’s one of the largest in the world.

Final Thoughts

We hope that helps you understand the different climate zones on Kilimanjaro. Armed with the knowledge that the weather changes dramatically through the different zones, you should be able to dress appropriately for your Kilimanjaro climb. For more info go here: https://kilimanjarosunrise.com/what-to-wear-on-kilimanjaro/